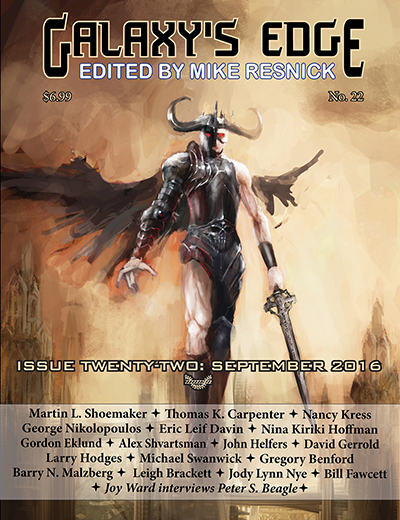

No title

FICTION

Bookmarked

by Martin L. Shoemaker

The Minotaur's Wife

by Thomas K. Carpenter

A Hundred Hundred Daisies

by Nancy Kress

A Human's Life

by George Nikolopoulos

In the Yucky Death Mountains

by Eric Leif Davin

Marrow Wood

by Nina Kiriki Hoffman

Another True History

by Gordon Eklund

Dante's Unfinished Business

by Alex Shvartsman

Turning the Town

by John Helfers

The Bag Lady

by David Gerrold

Manbat and Robin

by Larry Hodges

Legions in Time

by Michael Swanwick

INTERVIEW

Peter S. Beagle

by Joy Ward

SERIALIZATION

The Long Tomorrow (Part 5)

by Leigh Brackett

COLUMNS

From the Heart's Basement

by Barry N. Malzberg

Science Column

by Gregory Benford

Recommended Books

by Bill Fawcett & Jody Lynn Nye

THE PHOENIX PICK WEB-SITE

SIGN UP FOR FREE EBOOKS

One book per month offered by Phoenix Pick, (publisher of

Galaxy's Edge). Click Here

FREE EBOOK

LEST DARKNESS FALL

and Related Stories

Click Here

The Classic Story that

started a the alternate history subGenre...

Plus tribute stories by David Drake, S.M. Stirling and Frederi\k Pohl

Copyright © Arc Manor LLC 2016. All Rights Reserved. Galaxy's Edge is an online, digital and print magazine published every two months

(January, March, May, July, September, November) by Phoenix Pick, the Science Fiction and Fantasy imprint of Arc Manor Publishers.

ABOUT

ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING

SUBMISSIONS

CONTACT

THE EDITOR'S WORD

by

Mike Resnick

Welcome to the 22nd issue of Galaxy’s Edge. We’ve got a bunch of new stories for you by (mostly) new writers, including Alex Shvartsman, Larry Hodges, Thomas K. Carpenter, Eric Leif Davin, Martin L. Shoemaker, Gordon Eklund, George Nikolopoulos, and David Gerrold, plus some reprints by old friends Nancy Kress, Nina Kiriki Hoffman, John Helfers, and Michael Swanwick. And of course we have our regular features: Recommended Books by Bill Fawcett and Jody Lynn Nye; Gregory Benford’s science column; Barry Malzberg’s thoughts on literary matters; and this month Joy Ward interviews Peter S. Beagle.

*

So here’s the situation. Street and Smith, the giant pulp chain, also owns a radio show back in 1929, a mystery anthology show with no continuing characters except the announcer—and the announcer happens to be the one of the most popular characters on the air, a mysterious figure known only as the Shadow.

So someone at Street and Smith decides, just to make sure no one swipes the character, maybe they should put him in a one-shot pulp magazine, so they can prove that he’s copyrighted and that they own him.

They hire Walter Gibson, a guy who splits his time between being a nightclub magician and a pulpster, and pay him $500 to come up with a novel, which he does in a few weeks’ time. No one thinks much will come of it, and Gibson writes it as “Maxwell Grant,” possibly so it won’t be associated with his real name when he’s applying for magic gigs. Street and Smith accepts the manuscript, assigns the cover art, prints it, and that, they think, is that.

But the magazine sells out in near-record time, so they decide to make The Shadow a monthly, and Gibson is hired at $500 a novel to start churning them out. This is not bad pay in 1930, because the stock market crashed in 1929, the Depression is going full-force, and the average American is making about $1,200 a year—and about a quarter of the average Americans can’t find work.

So “Maxwell Grant” starts grinding out a Shadow novel a month, and Street and Smith publishes it—and suddenly more than a million people are buying each issue, and The Shadow is the hottest property they’ve got.

They can’t believe their luck, so they do nothing for a couple of years, and then they decide to go semi-monthly, since the magazine is still selling like hotcakes. They approach Gibson, tell him how much they love him and that they’re all one big happy family, and ask if he can turn out two Shadow novels a month. He says yes. Fine, they say; we’re in business. Just a minute, says Gibson; you’re selling millions of copies and making money hand over fist, so surely you can afford to give me a raise to $750 a manuscript.

Suddenly they don’t love him quite so much, and maybe he’s not really related to their big happy family after all. We’re paying $500, they say; take it or leave it.

If you don’t give me $750, says Gibson, I’m walking—and I’ll take my millions of readers with me.

Street and Smith laughs. (You didn’t know heartless corporations could laugh? Now you do.) You can leave, they say—but your audience is staying right here. Next month there will be a new Maxwell Grant and who will know the difference?

It takes Gibson about three seconds to realize that Street and Smith are holding all the cards, and he gives in and keeps writing $500 Shadow novels.

And the gentlemen running Street and Smith decide that they have lucked onto a pretty good policy. It is time to develop another “hero pulp”—which is to say, a pulp magazine with a continuing character. And after speaking with pulpster Lester Dent, they hit upon Doc Savage. Only this time it isn’t the author who decides to use a pseudonym; it is Street and Smith, who insist upon it, and henceforth all one hundred and eighty-some Doc Savage novels are to be written by “Kenneth Robeson,” just as the three hundred-plus Shadow novels are written by Maxwell Grant.

And rival publishers are not slow to notice just what Street and Smith is doing to combat inflation (for which read: avoiding paying a fair price to writers). Henceforth, although most of the Spider novels are written by Norvell Page, every one appears under the byline of “Grant Stockbridge.”

“Kenneth Robeson” is so popular as the author of Doc Savage that “he” also writes The Avenger series of pulps. The only author of a continuing hero pulp character who doesn’t have to put up with this is Edmond Hamilton, who is writing Captain Future novels for Better Publications, and the only reason why he doesn’t have to put up with it is because he is the only science fiction writer working for Better, and no one else there knows how to write this Buck Rogers crap.

Well, the last hero pulp died in the late 1940s, and that was the end of the practice for more than thirty years.

Now move the clock ahead, and wander over to the romance field, where a young woman named Janet Dailey began writing for Harlequin when she was thirty-one years old, and by the time she was thirty-seven she had sold a truly phenomenal total of one hundred and ten million paperbacks for them. They loved her, and they thought she loved them…

…and then Silhouette (which is now owned by Harlequin, but was its greatest rival back then) bought Janet and her millions of readers away.

And Harlequin swore this would never happen to them again, that they might lose a writer from time to time, but never the writer’s book-buying fans…and finally someone (or maybe someone’s grandfather) remembered the hero pulps—and suddenly, if you were a Harlequin writer, you were not allowed to use your real name…whereas if you wanted to sell them, you had to use a pseudonym.

Now, the world and the law had changed a little over the years, and Harlequin (and Silhouette, too, after Harlequin bought it) had to concede this much: only the author who first created the pseudonym could use it. If an author left, there wouldn’t be a new author writing under that name the next week…but the flipside was that Harlequin owned the pseudonym and the author couldn’t take it with her when she left.

That was the situation when my daughter, Laura—an award-winning fantasy writer these days—first broke into print as a romance writer. Her first fifteen or twenty novels were written by “Laura Leone.” There was a class action suit and settlement somewhere in the late 1990s and Harlequin reluctantly allowed authors to be themselves again.

But good ideas never die, they just hibernate from time to time. I would imagine publishers will be using this particular one to protect themselves and shaft writers at least once more during my lifetime.

ONE SALE NOW

ABOUT

ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING

SUBMISSIONS

CONTACT

Martin L. Shoemaker is a Writers of the Future winner. He has sold multiple times to Analog, plus stories to other top markets. This is his fourth appearance in Galaxy’s Edge. Martin was a Nebula nominee in 2016.

BOOKMARKED

by

Martin L. Shoemaker

“So why’d you turn off the lights, doctor? Are we done with the visual tests?”

Andrew heard Dr. Morgan answer from the darkness, though he wasn’t sure of her direction. “Visual cortex stimulation and neural mapping, Mr. Burns. And yes, it’s completed.”

“That was the last thing we had to record, right? So turn the lights on. Let me get dressed. Elena must be getting anxious in the waiting room.”

He heard the doctor sigh. That was followed by the sound of a coffee cup setting on a tray, but he couldn’t smell the coffee. Too bad, he hadn’t had any all morning.

Dr. Morgan finally answered. “The neural map was completed seven months ago.”

“What?” Andrew looked around, but the darkness was total. “No. I just laid down on your table a few hours ago.”

“I’m afraid not. Andrew Burns laid down upon our table seven months ago and went through a full-brain neural mapping. Then he and Elena went home, leaving us to process the recording. You are that recording, playing back on our simulated cerebral hardware.”

“Nonsense!” Andrew wondered if Dr. Morgan was stimulating irritation for the sake of the mapping. “What sort of game is this? I’m right here. I can feel this—” Wait. Andrew couldn’t feel the table. In fact... “I can’t feel my hands, my legs. I can’t even feel my tongue when I talk!”

Dr. Morgan’s voice dropped, low and calm. “That’s because you don’t have a tongue. You have a voice synthesizer, hooked into your simulated speech centers so that we can have conversations like this.”

“But then how can I hear you? I don’t have ears, right?”

“Microphones hooked into your auditory cortex.”

Andrew paused. “I’m asleep. I’m dreaming. This isn’t real.” Then he remembered the demonstration that Dr. Morgan had given him before he had agreed to the mapping procedure. “You said that you would communicate with—with it via text.”

“Yes, that’s exactly what we did during our early simian studies, the ones that... Andrew and Elena witnessed. We trained apes in simple sign language, mapped their brains, and then sent signs to those recordings via a text interface. But we’ve made some significant improvements since then.” She cleared her throat. “We... had to.”

“Had to?”

Dr. Morgan’s voice was slow, reluctant as she answered. “We found that your... playback... your wave patterns in the simulated cerebrum destabilized rapidly without audio input. If you couldn’t hear your own voice as you ‘spoke,’ your... holographic wave patterns... degraded. Quicker than expected.”

“What do you mean, you ‘found’ this? When did you run these tests? I don’t remember them. The last thing I remember was you flashing words and images onto a screen while I described what I saw and how I felt about it. You didn’t run any new tests.”

Dr. Morgan sighed again. “No new tests today, Mr. Burns. Except this one.” Andrew almost interrupted to ask her what test she meant, but she continued too quickly. “But this is not the first time we’ve... activated the cerebrum. Powered you up for playback.”

Andrew remembered a conversation from a few weeks earlier. (It was just a few weeks. He knew that, though doubts were settling in.) “You can’t run tests on me! That was clearly covered in the papers I signed. Your human subject protocols require my explicit permission for each new test. I haven’t given permission.”

Dr. Morgan spoke carefully. “If we were testing Andrew Burns, yes, we would have to have permission. But we’re not. You are just... data, and Andrew already signed all the paperwork necessary to give us full control of all data that we gathered from him. All you are... is a recording.”

“I am not!” Andrew felt outrage, like he hadn’t since the day he had received his cancer diagnosis. Yet it was different: this was a strong, deep revulsion, but without the racing heart and tremors he had felt. Elena had to calm him then; now his anger was passionless. Bloodless. “That was the whole point of your experiment: to record a personality so that you can transfer it into a new brain when cloning catches up. If I was a person and I will be a person in that new brain, then I am a person right now. Q.E.D.”

“Yes,” Morgan said. “That is our hope. But there has been no legal ruling regarding your status. You’re still our alpha test, the first recorded consciousness of a human subject. The law hasn’t caught up, can’t catch up until the courts have our results to consider. You are in...”

Dr. Morgan couldn’t finish her metaphor, but Andrew saw it coming. “...legal limbo.” He laughed, a bitter laugh that sounded mechanical in his ears. They must not have built a laughter simulator into his systems.

And just like that, Andrew knew: he believed Dr. Morgan’s story. Every word of it.

Morgan laughed lightly, sympathetically. “You’re a special case, a precedent setter. We do have protocols we must follow, reviews we must file; but as a practical matter, we can’t ask your permission before each test, because you’re... dormant until the test begins. You do not have the rights that Andrew Burns had.”

“Had?” If he’d had an eyebrow, he would’ve raised it.

“I’m sorry. Andrew Burns passed away two-and-a-half months ago from complications of his cancer.”

“Why didn’t you tell me this sooner?”

Andrew heard footsteps. Dr. Morgan was pacing. “Past experience has shown that we need to ease you into certain topics. It helps to slow your degradation.”

“There’s that word again: degradation,” Andrew said. “What do you mean by that?”

The pacing stopped. “We’re still learning. We’re one-hundred percent certain that we have successfully recorded your—Andrew’s personality. Your neural map is as complete as any we’ve ever created. But what we can’t do—yet—is impose that recording onto a new brain. Cloning isn’t even ready to produce a brain. Ten years out at the earliest. But when it is, we want to know that we can ‘play back’ your map into it. To learn how to do that, we play the map into our simulated cerebrum and see how well it transfers. But so far the answer is: not well enough. The holographic wave patterns degrade... Collapse.” Her voice caught, but then she continued. “And then we study what happened, look for ways to improve the transfer, and try again.”

“But why don’t I remember these tests?”

Morgan’s voice grew louder, as if she had approached the microphones. “We start each test fresh. You should understand that, you’re—Andrew was a science teacher. You know how important it is to start each test from the same known state, and only change one variable per test. That lets us assess the effects of one change at a time.”

“Of course,” Andrew agreed. He didn’t want to, but he couldn’t argue with the logic.

“We’re learning to maintain your playback, a little longer each time, but we have to be methodical about it. This is going to take a long time.”

“So... I’ve been through this before, I just don’t remember.”

“Yes,” Dr. Morgan said. “Sometimes more than once a day, during the past seven months.”

Andrew wished he could shake his head. “Couldn’t you... try letting me keep the memories? Let me have some sense of the passage of time?”

“I’m sorry. You ask this often, and my answer is always the same: We’ve considered it, but it’s too dangerous. We don’t know yet how the simulated long-term memory might affect your mapping. We might get it wrong, and... lose you completely. So we always go back to the known state.”

“It’s like I’m a...” Andrew paused, looking for a metaphor. “A bookmark. I hold your place so you can go back and start my story from the same place.”

“Yes.”

There was a long, uncomfortable pause. It lasted so long, Andrew wondered if his “ears” had failed. So he broke the silence. “So this is it. This is all I get, however much time you can keep me ‘playing back’.”

“Yes.”

“And how long is that?” he asked.

“I’d rather not say.”

Andrew mustered as much anger as he could. “How long is that, damn it?”

When Dr. Morgan spoke, it was in a soft, soothing voice. “Please trust me. You’ve asked this before, just like all of your other questions; and when we gave in and answered, it only created new stress. A sort of feedback oscillation. You mentally counted down the time, and you became less coherent by the minute. Usually the collapse came sooner when you knew. And once...” Andrew heard her swallow. “Once we had to shut you down prematurely. You were too distraught. It was... the kindest thing to do.”

“Maybe that’s what I want.” Andrew heard a petulant tone in his simulated voice (or maybe he imagined it). “If this is all I get, then maybe I should just get it over with. Just shut down.”

“Oh, no!” Morgan said in a rush. “Please, no! We’re getting better with every test. We’re giving you more and more time. Cybernetically and psychologically, we find ways to extend your playback. Sometimes a few seconds, sometimes several minutes. Someday... Someday you’ll be stabilized, I’m sure.”

“But not today.”

“No. Not today. It would take a miraculous breakthrough.”

Andrew answered drily, “I never allowed miracles in my classes. I can’t ask for one now.” He tried to see another answer, but he couldn’t. “So I have to die today so that in the future you can save some other Andrew Burns, keep him alive long enough to map him into a new body.”

“Don’t think of it as dying,” Dr. Morgan said. “Think of it like you said… a bookmark, a chance to go back to a known state.”

“You go back, but I don’t. Not this self.”

“A self does, an Andrew Burns indistinguishable from yourself.”

“But it’s not me. That recording, that’s not myself.”

“Scientifically, that’s exactly yourself. You are that recording. At some level you know that.”

“But I don’t experience the recording, I experience this. This now. This... darkness. Couldn’t you at least give me some light?”

“Not yet. The last time we tried, the visual experience was too jarring. You didn’t see your body, and your brain expected to, even though you should’ve known better. You collapsed almost immediately. We hope to try again next month, after we extend you a little longer.”

“You’re goddamn monsters!” Andrew said, wishing he could spit. “You kill me every night, and then resurrect me every morning to put me through it all again.”

“We’re not killing you,” Morgan answered. “It—collapse happens naturally, and we do our best to postpone it. We’re being as considerate as we can. You volunteered for this, remember?”

He had. It had been the only way that he could leave any money to Elena to help her deal with their bills. The cancer had made it impossible for him to return to teaching, and the bills had piled up. “You said I could help science,” he said, “and help Elena at the same time. And maybe someday... return to her in a new, healthy body.” At that thought, Andrew had a new idea.

“Doctor, please, can I see Elena? Or, well, talk to her before I go?”

Dr. Morgan tsked softly. “That would be a bad idea, I’m afraid.”

“Is everything a bad idea?” Andrew fumed, then continued. “She’s my wife! I did this for her.”

“I know,” Morgan said. “You love her very much. You want to take care of her, and you don’t want to see her get hurt any more, right?”

“Never.”

“Sometime after Andrew’s death, we brought her in to talk to you, and it hurt her. Very much. The strain was more than she could bear. She came once, and she sat with you through... to the end. The second day she lasted an hour before she had to leave. The third day she lasted only a few minutes before she broke down, and you begged us to get her out. Then you ordered us never to bring her back. Not while you’re unstable. I don’t think you want to change that order, do you?”

Andrew felt a twinge as if his nonexistent tear ducts would well up. “No, you’re right. I can’t do that to her. Can’t... make her watch me die again.”

“That’s for the best,” Morgan agreed.

“So... So what now?”

“Well... I won’t say how long you have left; but for as long as you’ve got, I want to sit here and talk to you. About whatever, it’s all good for our tests. You’ve told me so many stories already. Growing up in the woods, going to school, raising your kids. I want to hear it all.”

“So that... somebody will remember me.”

“Oh, no,” Dr. Morgan said. “It’s for the tests, really.”

“So you say.” Andrew wished he could offer her a reassuring smile. “This is difficult for you, isn’t it, doctor? To hell with what the science says, you’re human, you’re a good person. Watching me degrade is very hard on you.”

“Yes, Andrew.” He heard her swallow a sob. “But you do what you have to do.”

He hesitated. “I’d rather not put you through any suffering.”

“Oh, but please! You were just telling me about how you met Elena, and your first date, when you...”

“When I collapsed last time,” he finished. “How far did I get?”

“You had just washed your car, and you were pulling into her driveway and wondering how she would look.”

“I see. Well, I was plenty nervous when I got out of the car, walked to the door, and pressed the doorbell. But when she opened the door, and stood there... She was the most beautiful sight I have ever seen.” The recording paused for breath, but only out of habit, and then added softly, “Or ever will...”

4/21/2016—In memory of Dr. Philip Edward Kaldon

Always a teacher.

Copyright © 2016 by Martin L. Shoemaker

ON SALE NOW

Thomas K. Carpenter is the author of more than a two dozen novels, including seven in the popular Alexandrian Saga. This is his first appearance in Galaxy’s Edge.

THE MINOTAUR'S WIFE

In a forgotten diner somewhere on Route 550 between Albuquerque and Durango, a woman washes the counter with a rag so clean you’d think she’s in a commercial. The diner, once the ubiquitous way station of travelers fifty years before, sits on a patch of asphalt, surrounded by sage brush and time. In the parlance of tourists in their passing Toyota Siennas, the diner is a “greasy spoon,” but no one who’s ever eaten at this particular eating establishment ever calls it that.

The woman behind the counter has high cheekbones and the warm mocha skin that gets comments from her customers that assume she’s Navajo, since the reservation lies a moonbeam away. She goes by “Honey,” which is on her nametag, and everyone who’s ever dined in her establishment has mentally noted the precision of her movements around the counter and griddle.

For one, she doesn’t use a spatula, but a pair of chopsticks in each hand. She cooks eggs, bacon, sausage, nopales with chorizo and eggs, griddle cakes, chilaquiles, huevos rancheros, and a dozen other items listed on the one page menu. She moves with the grace of a martial arts grandmaster. Just a few months ago, a businessman with a Rolex watch and crooked smile offered her a job as a chef in an LA restaurant. She politely declined and gave him a meal on the house.

But Honey wasn’t the only interesting thing about the diner.

Every day and night, her husband the minotaur, sits in the corner booth facing the counter, his fingers dutifully dancing across the keyboard on his laptop. He’d filed his horns down to nubs years ago when he started flying coach. Otherwise, he looks like a guy who’d played linebacker in college, but let himself go since the glory days.

Honey is organizing the eggs in order of size when an older woman with streaks of gray and wearing a blue blazer enters the diner and sits at the center seat. This is the third time in the past week the woman has eaten at the diner.

Honey gives the woman a warm apple pie smile, the kind that makes her customers feel like family, and says, “Nopales with eggs and chorizo?”

The woman in the blue blazer’s face brightens. “You remembered.”

Honey looks the woman in the eyes. “I don’t get many repeat customers.”

The woman holds her hand out as if to introduce herself. The nails are perfectly manicured and the skin unblemished except for a few wrinkles.

“I’m Trisha.”

Honey ignores the hand and scoops a hunk of chorizo from a bowl onto the griddle. A serving of nopales hits the hot surface a moment later, sizzling and popping.

Trisha puts her hand back onto her hip. “I work at the Walmart in Nageezi but live in La Jara.”

“That’s quite a drive,” says Honey, keeping an eye on the woman.

Trisha makes a head motion towards Honey’s husband. “What’s the deal with him? I thought you didn’t get repeat customers.”

“He’s not. He’s my husband,” says Honey, and when Cyrillo looks up, she winks. He smiles and goes back to work.

“Cute,” says Trisha, clearly trying to sound casual. It’s almost working. “Didn’t think you could get Internet out here, my cell craps out about ten miles down the road.”

“Satellite dish,” says Honey. “It’s on the back of the diner, so you can’t see it from the front.”

Trisha looks back to Cyrillo. For a moment, she sees the horns. It’s brief, but Honey catches the recognition in her gaze.

“What’s he doing?” she asks, once again forced casual.

Honey cracks the eggs on the griddle, one in each hand. Using the chopsticks, she whips the eggs into a scramble like a miniature tornado. As they solidify, she scoots the chorizo and nopales into the eggs, continuing the mixing.

She takes a plate and corrals the egg, chorizo, and nopales mixture onto the clean white surface. She slides the meal to Trisha.

Honey knows Trisha is a government agent. She sees the glint of a warding amulet when Trisha’s shirt flexed around the buttons as she scooped eggs and chorizo into mouth. Which means that other agents aren’t far behind.

“Hacking the US government,” says Honey.

The woman chokes on her water, spilling liquid onto the counter as she sets the glass down.

“What? You can’t possibly be serious?” asks Trisha, one hand reflexively going to her hip again.

“I’m not a liar like you, agent whatever-your-name-is,” says Honey.

A moment of thought passes across the agent’s face as she considers her options. It’s clear Trisha didn’t expect things to unfold like they have. Then she stares with horror at the food she just ate.

“I didn’t poison you,” says Honey. “You can finish your meal.”

Trisha gives it a brief glance and then slides it back towards Honey.

Trisha asks, “What gave me away?”

“I’ve never seen a Walmart employee with such flawless hands. Stacking shelves isn’t easy work,” says Honey.

Trisha splays her fingers and looks at them as if they’ve betrayed her. When she puts her hands back into her lap, Honey speaks again.

“Your gun won’t work here, so don’t try. This is my land, so I get to set the rules. I’m guessing by your amulet, you already know that,” she says.

It’s not entirely true. A full clip could do some damage, enough to put a dent into Honey’s plans. But it would cost Trisha her life, and Honey knows the agent isn’t that loyal to the agency. It also gives Honey a little more time to figure out what to do.

Trisha nods, and puts her hands back onto the counter.

“What are you hoping to accomplish?”

Honey thinks about it. She considers not answering, but then after looking at her husband, she realizes their plan of escaping together has come to naught. The only thing she can hope to do is to salvage her goals.

“Revenge. A comeuppance. Maybe even karmic backlash, depending on your spiritual esthetic. Or if you prefer specifics, so you can put it in the report you’ll eventually have to write, my dearest husband is putting viruses in every department of every branch of government. A virus that when released will shut down every computer in the system rendering it unusable,” says Honey.

Trisha laughs, clearly believing the plan ludicrous, unbelievable. She looks back at Cyrillo again, but something about him puts doubt into her face. Just a little, in the form of a crinkle around the eyes.

“He couldn’t possibly accomplish that. The government uses the best encryption possible. They have tens of thousands of professionals, and not every system is the same. It would take a team of hackers decades to accomplish what you’re suggesting,” says Trisha.

“See my husband over there? You saw it for a moment before, but didn’t want to believe it. He’s a minotaur, one of the oldest, proudest creatures on this planet,” she explains.

Trisha squints at first, then her eyes widen. “I read the briefs, but I didn’t think it was true.”

“Believe it,” says Honey. “And he’s the best hacker on the planet. Do you want to know why? Because what is encryption?”

Trisha’s forehead wrinkles. “A method to protect data?”

“And how does it do that. It obfuscates, confuses, creates pathways that go nowhere. Essentially a maze,” says Honey. “So if you try and move on us, we’ll unleash the virus and shut down the government.”

The realization of what this means starts to dawn on the agent. She glances back to Cyrillo, and then her car, before turning back to face Honey. Then, because she’s a professional, she sits up straight and looks Honey in the eye.

“Look. I don’t think you understand the severity of your situation. We’ve been staking this place out for weeks now. We’ve got agents in both directions, and helicopters on standby. The only reason we haven’t come down on your hard is because we had to know that it was you. So even if you pull this virus thing off, you won’t get far, and I know the agency has people who can deal with people like him,” she says.

“At least you didn’t try to sell me with that ‘help us out and we’ll go easy on you’ business,” says Honey.

Trisha makes a little hitching motion with her head. “You did call me out as a liar earlier. I figured after the hospitality of not poisoning me, I could at least save you the trouble. You don’t seem like the type to be intimidated anyway. I’m just hoping pure logic will sway you from this path.”

Trisha’s hand on the counter is shaking. Honey smiles at it and says, “You can leave anytime. I’m not going to stop you.”

The agent lets out a breath. “I didn’t know what kind of plans you had for me.”

Honey crosses her arms and stares at the agent.

“Right,” says Trisha, getting off the stool and reaching for her purse.

“Don’t bother,” says Honey.

Trisha seems to consider the foolishness of offering to pay, especially after making threats, and nods. There’s no point of goodbyes. The agent leaves with one last furtive glance toward Cyrillo.

The agent’s car eventually backs onto the highway and speeds off in the general direction of Durango. Honey knows she has about twenty minutes before they return with the cavalry.

Cyrillo leans back when Honey strolls up, chopsticks in hands.

“All finished?” she asks, even though she knows the answer.

“No,” he says with his hands on the keyboard mid-type, shaking his head. “I’ll need a couple of more weeks for that.”

“How much?”

He gives a half-shrug, smiles wistfully. “About eighteen percent. I’ve got the Pentagon, and the Department of Agriculture, but you know the government and their agencies. It’s like walking through a maze.”

The joke is sweet and she smiles for him, despite the ache tearing a hole in her chest.

The reality hurts. She wants her revenge, her vengeance for how they lied to her people, killed them with the modern world. Making them slaves to slot machines and card tables.

There’s only one way she can salvage this...need. Honey leans over and kisses her husband on the forehead, right beside a nub. She knows what she has to do now. It’s the only way.

“Launch the virus,” she says, feeling a tightness in her chest.

He pauses, tilting his head.

“Just launch it. There’s no time to explain,” she says.

His fingers fly across the keyboard for a minute and then he glances up and nods. Honey swears she can hear sirens, even though it’s only been two minutes since Trisha left. Maybe she should have killed her, but at the time she didn’t think there was a way. Trisha probably had a CB radio in the car, Honey realizes.

With regret held tightly between her teeth, Honey moves closer.

“You were a perfect husband,” she says.

His forehead wrinkles at the past tense, but it’s too late. In one rapid, double-snap of her chopsticks, she cuts off the minotaur’s head and swallows it before it hits the floor.

She stares at his lifeless body, feeling pain well up in her chest. But it had to be done. Once he took control of the encryption, using his powers over mazes, he made every password and bio-scanner obsolete, rendering every system, machine, and terminal that he’d infected inert.

But they could make him take it back and she couldn’t allow that. Not after what they did to her people so long ago.

“Honey” leaves the diner through the back door with the chopsticks still in her hands. As she strolls across the hardpack, her arms rise into a rigid position.

A coyote howls in the distance, a sad cry of victory.

Clothes fall away, left in a strange pile that will confuse the agents when they search for her. By the time she reaches the edge of the light from her diner, she has transformed.

Between the sagebrush, a lone insect travels in a fastidious manner, arms held in a praying position. Inside her head, dreams of endless pathways rotate like fractals. She flees into the Navajo desert, where the people still walk with the gods.

Copyright © 2016 Thomas K. Carpenter

I hear him go out the front door. The wind had stopped, like it always does at sundown, and even though he was moving quiet as a deer, I’d been lying awake for this. My clock says 2:30 a.m. The hot darkness of my bedroom presses all around me. The front door closes and the motion-detector light on the porch comes on. We still have electricity. The light stays on ten full minutes, in case of robbers.

Like we have anything left to steal.

I’m ready. Shoes and jacket on, window open. After supper I took the sensor out of the motion light on the west side of the house. My father doesn’t notice. He’s headed the other way, toward the road.

Out the window, down the maple tree, around the house. He’d parked the truck way down the road, clear past the onion field. What used to be the onion field. Quietly I pull my bicycle, too old and rusty to sell, out from my mom’s lilac hedge. No flowers again this year.

The truck starts, drives away. I pedal along the dark road, losing him at the first rise. It doesn’t matter. I know where he’s going, where they’re all going, where he thought he could go without me. No way. I’m not a child, and this is my future, too.

Somewhere in the roadside scrub a small animal scurries away. An owl hoots. The night, so hot and dry even though it’s only May, draws sweat from me, which instantly evaporates off my skin. There are no mosquitoes. I pedal harder.

*

Allen Corporation has posted a guard at the construction site, where until now there has been no guard, nor a need for one. Did someone tip them off? Is the law out there, with guns? I’ve beaten my father to the site, which at first puzzles me, and then doesn’t. He would have joined up with the others somewhere, some gathering place to consolidate men and equipment. You couldn’t just roar up here in a dozen pickups and SUVs, leaving tracks all over the place.

A single floodlight illuminates the guard, throwing a circle of yellow light. He sits in a clear, three-sided shack like the one where my sister Ruthie waits for the school bus with her little friends. I can see him clearly, a young guy, not from here. At least, I don’t recognize him. He’s got on a blue uniform and he’s reading a graphic novel. He lifts a can to his mouth, drinks, goes back to the book.

Is he armed? I can’t tell.

A thrill goes through me, starting at my belly and tingling clear up to the top of my head. I can do this. My father and the others will be here soon. I can get this done before they arrive.

“Hey, man!” I call out, and lurch from the darkness. The guard leaps to his feet and pulls something from his pocket. My heart stops. But it’s not a gun too small. It’s a cell phone. He’s supposed to call somebody else if there’s trouble.

“Stop,” he says in a surprisingly deep voice.

I stop, pretend to stagger sideways, and then right myself and put on what Ruthie calls my “goofy head” weird grin, wide eyes. I slur my words. “Can I ha’ one o’ those beers? You got more? I’m fresh out!”

“You are trespassing on private property. Leave immediately.”

“No beer?” I try to sound tragic, like somebody in a play in English class.

“Leave immediately. You are trespassing on private property.”

“Okay, okay, sheesh, I’m going already.” Now I can make out the huge bulk of the pipeline, twenty feet beyond the guard shack. I stagger again and fall forward, flat on my face, arms extended way forward so he can see that my hands are empty. “Aw, fuck.”

The guard says nothing. At the edge of my vision I see him finger the cell. He doesn’t want to look like a fool, calling in about one drunken kid, waking up Somebody Important at three in the morning. But he doesn’t want to make a mistake, either. I help him decide. I turn my head and puke onto the ground.

This is a thing I learned to do when I was Ruthie’s age: vomit at will without sticking a finger down my throat. I practiced and practiced until I could do it anytime I wanted to impress my friends or get out of school. So I lay there hurling my cookies, and I’m not a big guy: five-nine and one hundred and forty-five pounds. Middle-weight wrestling class.

The guard makes a sound of disgust and moves closer. Clearly I’m no threat. “Get out of here, you fag. Now!”

I flail feebly on the ground.

“I said get out!” He yells louder, like that might sober me, and moves in for a kick. When he’s close enough, I spring. He’s bigger and older, but I was runner-up for state wrestling champion. Before he knows it, I’ve got him on the ground. Illegal hold, unnecessary roughness, unsportsmanlike conduct: two penalty points.

He shouts something and fights back, even though that increases his pain. I’m not sure I can hold him; he’s strong. I hear a truck in the distance.

The guy is going to get free.

My father will be here any minute.

Adrenalin surges through me like a tsunami.

The ground is littered with construction-site rubble. I pick up a rock and bash him on the head. He drops like a fifty-pound sack of fertilizer, and that throws me off balance. I go down, too, and my head strikes some random piece of metal. Everything blurs except the thought Oh God what if I killed the fucker? When I can see again, I drag myself over to him. Blood on his head, but he’s breathing. I’ve dragged myself through my own vomit. The truck halts.

Men rush forward. My father says, “Danny?”

“Christ, Larry, what is this?” Mr. Swenson, who farms next to us. Used to farm next to us.

I gasp, “Took.. out guard…for you.”

“Oh, fuck,” somebody else says. And then, “Kid, did he see your face?”

The answer must have been on my own face, because the man snaps, “You couldn’t have worn a ski mask?”

“Shut up, Ed,” Mr. Swenson says. I can’t get out my answer: I didn’t know there’d be a guard! Someone is bending over the guard, lifting him in a fireman’s carry. Someone else is pulling back my eyelids and peering at my eyes a doctor? Is Dr. Radusky here? No, he wouldn’t…he can’t…Things grow fuzzier. I lose a few minutes, but I know I’m not passed out because I’m aware of both my father kneeling beside me and parts of the argument floating above:

“— do it anyway!”

“—Larry’s kid screwed us and—”

“We came here to—”

“The law—”

“I’m not leaving until I do what I come for!”

They do it, all of them except Dad. Quick and hard, panting and grunting. The night shrieks with pick-axes, chain saws, welding torches. Someone moves the floodlight pole closer to the pipeline.

The huge pipe, forty-eight inches in diameter and raised above the ground on stanchions to let animals pass underneath, is being wrecked. Only a thirty-foot section of its monstrous and unfinished length, but that’s enough. For now. I hear a piece of heavy equipment, dozer or backhoe, start up, move. A moment later, a crash.

More pipe down.

It’s over in twenty minutes, during which I vomit once more, this time unwilled. Puking again blurs my vision. When it clears, my father is pulling me to my feet. I stagger against him. Before someone kills the floodlight, I see the Allen Corporation Great Lakes Water Diversion Pipeline lying in jagged pieces. I see dust covering everything to an inch thick and still falling from the sky, like rain. I see the farm the way it was when I was Ruthie’s age, the corn green and spiky, Mom’s lilacs in bloom, the horse pasture full of wildflowers. I see my dead grandfather driving the combine. I know then that my head hasn’t cleared at all, and that I am hallucinating.

But one thing I see with total clarity before I pass out: my father’s grim, tight-lipped face as he half-carries me to the pick-up full of men.

*

The law is at our house by 6:30 a.m.

Before that, Dr, Radusky came by. He made me do various things. “Concussion,” he said, “consistent with falling off his bicycle and hitting his head. Keep him awake, walking around as much as you can, and bring him to my office tomorrow for another look-see. No school today or tomorrow, and no wrestling for longer than that.” He didn’t look at my father, but Dr. Radusky knew, of course. The whole town knew.

“Larry,” my mother says in the hallway beyond my bedroom. They’re taking turns making sure I sit up, walk around, and don’t sleep. “Sheriff is downstairs.”

“Uh-huh.” My father leaves.

My mother comes into my room and snaps, not for the first time, “What in Christ’s name were you thinking?”

I don’t answer. If they don’t see that I’m a hero, the hell with them.

“I’m going downstairs,” she says. “Don’t lie down, Danny. Promise me.”

I nod sullenly. As soon as she’s gone, Ruthie slides in. She’s dressed for school in jeans and an old green blouse that used be Mom’s. It’s been cut down somehow to sort of fit her. “Danny,” she whispers, “what did you do?”

“Nothing, squirt.”

“But everybody’s mad at you!”

“I was out riding my bike and fell off it and hit my head. That’s all.”

“Out riding in the night? Why?”

“You wouldn’t understand.” My head throbs and aches.

“Were you going to see a girl?”

I wish. “None of your business.”

“Was it Jenny Bradford?”

“Beat it, squirt.”

“I’m going to go downstairs and listen.”

“No, you’re not!”

“If I don’t, then will you tell me another picture?”

Ruthie scavenges photographs. She ferrets them out of the boxes and envelopes where Mom has shoved them, hidden all over the house because Mom can’t bear to look at them anymore. I remember her doing it, crying as she ripped some from their frames there used to be a lot of framed pictures all over the place and tossed the silver frames into the box for the pawnshop. Now Ruthie finds them and brings them to me to identify things: That’s Great Uncle Jim in front of the barn we sold to the Allen people, that’s Grandpa driving the combine. She doesn’t remember any of it, but I do.

She pulls a picture from under her blouse and holds it out to me. This one is newer than most of her stash, printed on a color printer from somebody’s digital camera. I remember that printer. We sold it long ago, along with everything else: the antiques handed down from Great-Grandma Ann, the farm equipment, the land. None of it was enough. The house is in foreclosure.

I say, “That’s our old horse pasture.”

“We had horses?”

“One horse.” White Foot. He’d been mine.

“Where’s the horse?”

“Gone.”

“Where’s the pasture? Is it the dirt field over by the falling-down fence?”

“Yeah.”

“But what are those?” She points at the photograph.

In the picture the pasture, its fences whole and white-washed, is full of wildflowers, mostly daisies. Wave after wave of daisies in semi-close-up, their centers bright yellow like little suns, their petals almost too white, maybe from some trick of the camera. When was the last time I saw a daisy? Had Ruthie ever seen one?

I say, “Fuck, fuck, fuck.”

“You just said bad words!”

“They’re called ‘daisies.’ Now go away, brat.”

“You said bad words! I’m telling!”

Heavy footsteps on the stairs. Ruthie, looking close to tears, thrusts the photo under her blouse and skitters out the door. It isn’t the tears that do me in, it’s the blouse.

My parents come in, with Sheriff Buchmann. The room is too full. I know from her face that Mom hates Buchmann seeing my patched bedspread, faded curtains, sparse furniture. Me, I just hate the sheriff.

He says, “Daniel, did you go last night to the site of the Allen Corporation’s pipeline?”

“No, sir.”

“How’d you get that bandage on your head?”

“Tripped in the dark and fell off my bike.”

“Where?”

“Corner of Maple and Grey.”

“And what were you doing down there?”

“I had a fight with my father and wanted to get away.”

“What was the fight about?”

“My grades. My teacher called yesterday. My math grade sucks.” Could Buchmann tell I’d been rehearsed? He’d check, but Mr. Ruhl did call yesterday, and my math grade does suck. My parents gaze at me steadily, without emotion. They’re good at that. So is Buchmann. I want to ask if the pipeline guard is okay, but I can’t. I wasn’t there. It never happened. Unless the guard can I.D. me.

I gaze back, emotionless, my father’s son.

*

Ruthie is drawing daisies. I don’t know where she got the paper. Her crayons are only what’s been hoarded for years, now stubby lengths of yellow and green laid carefully on the kitchen table. So far she’s covered three sheets of thin paper with eight daisies each, every flower in its own little box. They have yellow centers, green leaves, and petals that are the white of the paper outlined in green.

“Hi, Danny! Is your head better?”

“Yeah. What are these?”

“Daisies, stupid.”

“I mean, why are you making them?”

“I want to.” She looks up at me, crayon stub in her fist, her face all serious. “Do you know what my teacher taught us in school today?”

“How would I know? I’m not in the second grade.” Unlike me, Ruthie likes school and is good at it.

“She taught us about the pipeline. Some people broke it Monday night.”

My hand stops halfway to the fridge handle, starts again, opens the fridge door. Nothing to eat but bread, leftover potatoes, drippings, early strawberries Mom picked today. She will be saving those.

Ruthie says, “The pipeline people are fixing it. It’s supposed to carry water to ‘The Southwest.’” She says the words carefully, like she might say “Narnia” or “Middle Earth.”

“Is that so,” I say. I take bread and drippings from the fridge.

“Yes. The water will come from ‘Lake Michigan.’ That’s one of the Great Lakes.”

“Yeah, I know.”

“There are five Great Lakes, and they have four-fifths of the fresh water in the world. That means that if you put all the fresh water in the world into five humongous pots, then four ”

I stop listening to her math lesson. The guard couldn’t I.D. me. I watched him on TV we still have a TV, so old that nobody wants it, but no LinkNet for any good programs. The guard looked even younger than I remembered, no more than a few years older than me. He also looked more scared than I remembered. I spread drippings on my bread.

Ruthie is still reciting. “The water is supposed to go to farms around the ‘Great Lakes Basin,’ but it’s not. It’s going to go through the big pipe to ‘The Southwest.’ Danny, why can’t we have some of that water to make our farm grow again?”

“Bingo.”

“Answer me!” Ruthie says, sounding just like Mom.

“Because the Southwest can pay for it and we can’t.”

Ruthie nods solemnly. “I know. We can’t pay for anything. That’s why we have to move. I don’t wanna move. Danny where will we go?”

“I don’t know, squirt.” I no longer want my bread and drippings. And I don’t want to talk about this with Ruthie. It fills me with too much rage. I put the half-eaten bread in the fridge and go upstairs.

The next night, the pipeline is attacked in Fuller Corners, twenty miles to the south. There are two guards, both armed. One is killed.

*

“Daniel Raymond Hitchens, you are under arrest for destruction of property, trespass, and assault in the first degree. You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used against you in court. You have the right to an attorney—”

The two cops, neither from here, have come right into math class during final exams. They cuff me and lead me out, my test paper left on my desk, half the equations probably wrong. My classmates gape; Connie Moorhouse starts to cry. Mr. Ruhl says feebly, “See here, now, you can’t—” He shuts up. Clearly they can.

Outside the classroom they frisk me. I bluster, “Aren’t I supposed to get one phone call?”

“You got a phone?”

I don’t, of course gone long ago.

“You get your call at the station.”

They take me to the police station in Fuller Corners. There is a lot of talking, video recording, paperwork. I learn that I am suspected of killing the guard in the Fuller Corners attack. The surviving guard identified me. This is ridiculous; I have never even been to Fuller Corners. That doesn’t stop me from being scared. I know that something more is going on here, but I don’t know what. When I get my phone call to my father, I am almost blubbering, which makes me furious.

My parents come roaring down to Fuller Corners like hounds on a deer. Along with them come more TV cameras than I can count. More shouting. A lawyer. I can’t be arraigned until tomorrow. What is arraigned? It doesn’t sound good. I spend the night in the Fuller Corner lockup because I’m seventeen, not sixteen. The jail has two cells. One holds a man accused of raping his wife. The other has me and a drunk who snores, sprawling across the bottom bunk and smelling of booze and piss. He never wakes the entire time I’m there.

*

Dad drives me home after the arraignment. I am out on bail. More TV cameras, even a robocam. I recognize Elizabeth Wilkins, talking into a microphone on the courthouse steps. She looks hot. Everyone follows my every move, but in the truck it’s just my father and me, and he doesn’t look at me.

He doesn’t say anything, either.

We drive through the ruined land, field after field empty of all but blowing dust. The thing that gets me is how fast it happened. We learned in school about the possible desertification of the Midwest from global warming. But it was only one possibility, and it was supposed to take decades, maybe longer. Then some temperature drop somewhere in the Pacific Ocean the Pacific Ocean, for fuck’s sake changed some ocean currents, and that brought years of drought, ending in dust that blew around from dawn to sundown. Ending in grass fires and foreclosures and food shortages. Ending in Fuller Corners.

Finally my father says, “This is just the beginning.” He keeps his eyes on the road. “But not for you, Danny. You’re not going to prison. If that’s what you’re thinking, get it out of your mind right now. Not going to happen. They got nothing but made-up evidence that won’t hold up.”

“Then why was I arrested?”

“PR. Yeah, you’re the poster boy for this. Bastards.”

On the courthouse steps, Elizabeth Wilkins said into her microphone, “The protestors are even using their children in a shameful and selfish fight to stop the pipeline that will save so many lives in the parched and dying cities of Tucson and—”

I am not a child.

“Dad,” I blurt out, “were you at Fuller Corners?”

His eyes never leave the road, his expression never changes, he says nothing. Which is all the answer I need.

I thought I knew fear before. I was wrong.

*

At home, Mom is frying potatoes for dinner. It’s warm outside but all the windows are shut against the dust, and all the curtains are drawn tight against everything else. Ruthie lies on the kitchen floor, frantically coloring. I go upstairs and sit on the edge of my bed.

A few minutes later Ruthie comes into my room. She plants herself in front of me, short legs braced apart, hands clasped tight in front of her. “You were in jail.”

“I don’t want to talk about it. Go away, squirt.”

“I can’t,” she says, and the odd words plus something in her voice make me focus on her. When she was littler, she used to go stand on her head in the pantry and cry whenever anyone wouldn’t tell her something she wanted to know.

“Danny, did you break the pipe?”

“No,” I say, truthfully.

“Are more people going to break the pipe more?”

“Yes, I think so.” Just the beginning.

“An ‘eviction notice’ came today while you were in jail. Does that mean we have to move right away?”

“I don’t know.” Is the timing of the eviction notice with my faked-up poster-boy arrest just coincidental? How would I even know? The people building the pipeline, which is going to be immensely profitable, are very determined. But so is my father.

Ruthie says, “Where will we go?”

“I don’t know that, either.” The Midwest is a dust plain, the Southwest desperate for water, the Great Lakes states and Northeast defending their great treasures, the lakes and the Saint Lawrence Seaway. Oregon and Washington have closed their borders, with guns. The South is already too full of refugees without jobs or hope.

Ruthie says, “I think we should go to Middle Earth. They have lots of water.”

She doesn’t really believe it; she’s too old. But she can still dream it aloud. Then, however, she follows it with something else.

“It will be a war, won’t it, Danny? Like in history.”

“Go downstairs,” I say harshly. “I hear Mom calling you to set the table.”

She knows I’m lying, but she goes.

I go into the bathroom and turn on the sink. Water flows, brown and sputtery sometimes, but there. We have a pretty deep well, which is the only reason we’re still here, the only reason we have electricity and potatoes and bread and, sometimes, coffee. I’ve caught Mom filling dozens of plastic gallon bottles from the kitchen tap. Even our small town, smaller now that so many have been forced out, has a black market.

I turn off the tap. The well won’t hold much longer. The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin Water Resources Compact won’t hold, either. Lake levels have been falling for more than a decade. There isn’t enough, won’t be enough, can’t be enough for everybody.

I go down to dinner.

*

Exhausted from two nights of sleeplessness and two days of fitful naps, I nonetheless cannot sleep. At 2:00 a.m. I go downstairs and turn on the TV. Without LinkNet, we get only two stations, both a little fuzzy. One of them is all news all the time. With the sound as low as possible, I watch myself being led from the jail to the courthouse, from the courthouse to our truck. I watch film clips of the dead guard. I watch an interview with the guard I clobbered with a rock. He describes his “assailant” as six feet tall, strongly built, around twenty-one years old. Either he has the worst eyesight in the county or else he can’t admit he was brought down by a high school kid who can’t do algebra.

Not that I’m going to need algebra in what my future was becoming.

When I can’t watch any more, I go into the kitchen. I gather up what I find there, rummage for a pair of scissors, and go outside. There is no wind. Dad’s emergency light, battery-run and powerful enough to illuminate the entire inside of the barn we no longer own, is in the shed. When I’ve finished what I set out to do, I return to the house.

Ruthie is deeply asleep. She stirs when I hoist her onto my shoulder, protests a bit, then slumps against me. When I carry her outside, she wakes fully, a little scared but now also interested.

“Where we going, Danny?”

“You’ll see. It’s a surprise.”

I’m forced to continue to carry her because I forgot her shoes. She grows really heavy but I keep on, stumbling through the dawn. At the old horse pasture I set her on a section of fence that hasn’t fallen down yet. I turn on the emergency light and sweep it over the pasture.

“Oh!” Ruthie cries. “Oh, Danny!”

The flowers are scattered all across the bare field, each now on its own little square of paper: yellow centers, white petals outlined in yellow, green leaves until the green crayon was all used up and she had to switch to blue.

“Oh, Danny!” she cries again. “Oh, look! A hundred hundred daisies!”

It will be a war, won’t it? Yes. But not this morning.

The sun rises, the wind starts, and the paper daisies swirl upward with the dust.

by

Thomas K. Carpenter

ABOUT

ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING

SUBMISSIONS

CONTACT

George Nikolopoulos hails from Athens, Greece. He’s written for SF Comet, Unsung Stories, Bards & Sages Quarterly, and elsewhere, both here and in Greece. This is his first appearance in Galaxy’s Edge.

A HUMAN'S LIFE

by

George Nikolopoulos

So, you have finally given in to your children’s desperate pleas for a pet, and they’ve persuaded you to get a human. A great choice for a pet—but there are a few things that you should know before picking one. First things first: Adopt a stray, don’t buy; there are several important reasons for this.

Humans are exotics, which means that they’re not a native species of our world or even, in fact, our star system. Capturing wild humans on their planet, Aerth, has been banned for several hundred years. This makes all humans descendants of the ones that were captured centuries ago, brought to Pandaesia, and domesticated. Pet stores and human breeders would have you buy purebred humans, and this of course leads to inbreeding. That’s why humans bought in pet stores are sicklier and live fewer years than strays. Purebred humans suffer from limited gene pools and have breed-specific health issues. Diabetes, hernia, bad back, and mental illness often plague the purebreds.

Commercial breeding facilities put profit above the welfare of humans. Babies are housed in appalling conditions, often becoming very sick and emotionally troubled as a result. The mothers are kept in cages to be bred over and over for years, and when they’re no longer profitable, they are abandoned or even killed. Most humans sold to unsuspecting consumers in pet stores come from such facilities.

Each year, millions of unwanted homeless humans end up at shelters across Pandaesia. Shelters keep them off the streets, where they’re admittedly a nuisance; males fight each other all the time, and marauding human packs are really dangerous. Half of these humans will have to be euthanized, for a simple reason: too many humans and not enough good homes. And yet the number of euthanized humans would be dramatically reduced if people adopted pets instead of buying them. We have to prevent breeders from bringing more humans into a world where there are already too many.

That’s why you should neuter your human. Don’t listen to the soft-hearted who will tell you it’s cruel. A neutered human is a happy, carefree human, delivered from its constant obsession with sex, and if you own more than one you’ll be amazed at how much better they will get along after being neutered. Neutering will also prevent several undesirable sexual behaviors such as humping, aggression, and the need to roam, as well as the messiness of the female cycle. Don’t add new strays to the world. Humans have a litter of only one every nine months, but they are in heat constantly, and this makes them really hard to control. Also, mothers are obsessed with keeping their cubs, and they are so persistent that you might end up with a whole human family on your hands—and believe me, that’s a bit more than you bargained for.

Humans are not toys; they are real live animals. Owning them is both a privilege and a responsibility. Generally, they live long—several decades—and, as cute and adorable as the babies are, there’s a tendency to abandon old ones in the streets. You must understand that a well fed, well cared-for human could live more than a hundred years. So when you get one, you must understand you get them for life. They will give you satisfaction and rich rewards, and when your human passes away you will be understandably sad—but please don’t ditch them when you’re bored of them.

You should play with your human for at least fifteen minutes every day, and you should groom it and keep it clean. Some people like to feed them table scraps, but if you do you should be careful to absolutely avoid foods that contain arsenic or polonium, and I should say that mercury is not a good idea either. There are several kinds of pellets suitable for a healthy and tasty diet, but again you should avoid the ones containing even traces of arsenic; they are cheaper, but they may be fatal to your human.

You can train your human to respond to a whistle when it’s time to feed it. They can even understand simple commands if you speak slowly, but you should never forget that, despite their modicum of intelligence, humans are animals and not people.

Copyright © 2016 George Nikolopoulos

LIMITS

Larry Niven

An extraordinary mix of fantasy and science fiction from one of the masters of science fiction, Larry Niven.

ABOUT

ARCHIVES

ADVERTISING

SUBMISSIONS

CONTACT

Eric Leif Davin, a science fiction historian, is the author of two books about science fiction Partners of Wonder: Conversations with the Founders of Science Fiction, and Partners in Wonder: Women and the Birth of Science Fiction, 1926-1965. This is his third appearance in Galaxy’s Edge.

IN THE YUCKY DEATH MOUNTAINS

by

Eric Leif Davin

The blazing sun was settling behind the jagged peaks of the Yucky Death Mountains, and the shimmering summer heat had at last given way to a cool breeze. Dust covered the pilgrim robes of the man and woman slouched in the donkey cart. Soon wolves would be howling from the shadows. The man flicked the reins to hurry their plodding donkey along. Dust powdered up from the back of the tired animal. It ignored the flicking reins and continued to clip-clop along at its same stolid pace.

The woman turned to her husband. “We’re lost,” she said.

“Nonsense, Hildegard. I know exactly where we are!”

“Utthar, you should’ve asked that peasant for directions back at the crossroads.”

“I don’t need directions. I know where we are.”

“So do I. We’re in the Yucky Death Mountains. And we’re lost.”

Hildegard knew she was right, but Utthar would never admit it. There were certain things men just did not do. They’d rather be lost in the Yucky Death Mountains with wolves howling in the distance than admit they were lost. Or ask for directions. Real men didn’t ask for directions. They always knew where they were, even when they didn’t. It was Male Knowledge Syndrome. Men could never admit they didn’t know something. After twenty years of marriage, it still infuriated her.

They were on their way to the Holy Land. It was Utthar’s idea, not hers. He’d had a vision, he said. An angel had come to him in the night and told him to sell their hovel in the village and go on a pilgrimage. Hildegard had protested, stormed, raged, to no avail. Utthar was determined to go, and he sold their hovel that very day. Then, with most of what he got for the hovel, Utthar bought a cart and a old donkey to pull it.

“And what are we going to live on during this pilgrimage of yours?” Hildegard asked when he returned.

“The Lord will provide,” Utthar answered.

Hildegard sighed. “He hasn’t been doing such a good job up to now.” Nevertheless, she loaded the cart with their meager possessions and they set out for the Holy Land.

On the second day they came to the Great Dismal Swamp with its Great Sucking Swampthings. Utthar decided to avoid that morass and turned them towards firmer ground.

On the third day they came to the Forest of Doom. Utthar decided to avoid that dark wood and its Predatory Mobile Trees with their prehensile limbs. Instead, he took them through the Yucky Death Mountains. And now they were lost in those yucky mountains. This pilgrimage is going to take forever, Hildegard thought glumly.

As dusk deepened into night they came upon the squalid inn. Their donkey pulled them to the old inn door and stopped, its job done. A sign with peeling paint above the inn’s door swung, squeaking, in the evening breeze. “Ye Olde Cesspool,” it read in crudely drawn letters. Utthar and Hildegard clambered down from the cart and approached the door. They paused to read the faded lettering arching above it: “Abandon all hope, Ye Who Enter Here.”

“Perhaps we’d best keep going,” Hildegard said.

“And be food for wolves? This can’t be as bad as it looks.”

Utthar pushed open the door. They recoiled from the Reek of Wrongness that assailed them, then recognized it as merely the pungent scent of sour wine. They stepped into the dark interior and saw a scene of utter devastation. Broken tables and chairs lay everywhere. The bodies of burly men sprawled across the floor. To Hildegard’s eye they all appeared to be Minions of the Dark Lord. Obviously there’d been a Tavern Brawl that had claimed numerous casualties. Utthar and Hildegard hesitated, uncertain whether to enter or leave. In the distance behind them a wolf howled. They entered.

Snores filled the air and they realized the Minions on the floor weren’t dead. Hildegard picked up a wine-stained postcard from the litter of broken glass and other debris on the floor. A fierce gang of heavily armed and shaggy-haired warriors were brandishing their swords with savage glee. Along the bottom it read, “Vacation in the Yucky Death Mountains, home of the Chain Gang. Bring Your Valuables!” Hildegard shuddered and dropped the postcard to the floor.

They walked warily across the room to the bar, their feet sticking in the gummy residue of the spilled wine. Behind the counter a scrawny barkeep in a soiled apron was stretched out on the floor. Hildegard leaned over and cleared her throat. “Uh, excuse me, sir, can you tell us which way to the Holy Land?”

The barkeep grunted, opened his eyes, and reached for the counter, pulling himself painfully up. He leaned across the bar, thrusting his filthy visage toward her. She recoiled from his fetid breath as a snaggletooth grin spread across his face. “Heh, heh, heh,” he cackled. “Sorry, mi’lady, but you can’t get thar from here!” Then he slapped the counter loudly and yelled to the room. “Wake up, Minions! We got company!”

The snoring bodies on the floor around them stirred and came to life. Some climbed groggily to their feet and stumbled toward the cowering couple. A particularly large and hairy denizen planted himself between them and the door and glowered at them. Utthar felt that queasy feeling you usually get about five minutes before you die. The barkeep cackled again and said, “Welcome to the Chain Gang, pilgrims!”

Utthar glared at Hildegard and said, “See? This is why men don’t ask for directions!”

But he knew he should’ve turned right instead of left at that last crossroads.

*

“Now, gentlemen,” Utthar said to the rough barbarians surrounding them. “We mean you no harm. We’re just seeking lodging for the night and directions to the Holy Land.”

The Chain Gang laughed heartily. “They mean us no harm!” one howled. “That’s a good’un! I was shakin’ thar for a minute!”

A short, muscular, bearded member of the gang stalked toward Utthar with a drawn dagger. He stuck it under Utthar’s chin until the point dimpled the skin and backed Utthar up against the wall. Utthar thought he might be a Dwarf, except that Dwarves were seldom seen outside the Dwarven Fastness deep inside the Yucky Death Mountains. “Stop staring at me all pop-eyed,” the perhaps-Dwarf demanded. “Ain’t ya never seen a Dwarf before? Now hand over your purse!”

Utthar fumbled at his belt and untied his purse strings. The knife still digging into his chin, Utthar handed over his purse. The Dwarf snatched it and spun away to a nearby stool. Utthar felt his chin where the dagger had dug into it. There was a drop of blood on his fingers.

The rest of the Chain Gang crowded around the stool as the Dwarf dumped out the contents of Utthar’s purse. Three thin coppers and a Widow’s Mite tumbled out onto the stool with dull thuds.

“Curse you!” the Dwarf yelled, turning back to Utthar. His dagger came up in Utthar’s direction. “Where’s the rest of your valuables? Where’s your credit cards? Your traveler’s checks?”

Utthar cowered back against the wall. “That’s all we have. It took most of what we had to buy the donkey and cart outside. We’re just poor pilgrims on the way to the Holy Land.”

“God’s Blood!” the Dwarf roared. “We haven’t had anyone to loot in a fortnight!”

“Well, it’s no wonder,” Hildegard interrupted, “considering the kind of welcome you give strangers.”

The ruffians turned toward Hildegard, standing in the middle of the room.

“Well, now,” the Dwarf said, as the Chain Gang closed in a circle around Hildegard. “What have we here? Might you be a Virgin?”

“Hmmpf! Do I look like a Virgin?”

The Chain Gang looked her over. “Well,” the Dwarf said, “you’re a bit plump and middle-aged to be a Virgin, but one could always hope. That’d double your price when we sold you to the Slavers.”

“You’re twenty years too late for that. Although it has been awhile.” Hildegard cast an accusing glance in the direction of her husband.

The Dwarf slapped Utthar’s empty purse to the floor and stomped on it. “Well, gol-durn it! He’s got no loot and she’s not a Virgin! They’re completely useless!”

“Hold on, thar,” the barkeep broke in. “Not completely. We could use a cook. I’ll wager she’s a good cook, as she looks like she eats well. And that one,” he gestured at Utthar, still up against the wall, “he can muck out the cesspool. It’s starting to overflow.”

The Dwarf eyed Hildegard. “Aye, she looks like she hasn’t missed too many a meal. Take her into the kitchen and see what she can do.” He turned to Utthar. “You! Think you could make yourself useful out back?”

“Oh, yes, I know how to use a muckrake.”

“Well, then, get to it!” The Dwarf grabbed Utthar by the arm, swung him around, and gave him a hard kick toward the door. Utthar staggered out, closing the door behind his behind.

*

The kitchen was a dark and scummy place. There was rancid organic matter decomposing on the floors and a black carbonized crust covered the pots and pans that lay scattered about. On a wooden cutting table in the center was a half loaf of hard stale bread next to a hunk of hardened cheese.

“This doesn’t look too promising,” Hildegard said. She walked around peering into nooks and crannies. As she did so, she tossed a question toward the scrawny barkeep, standing in the doorway. “That Dwarf out front with the pointy dagger. What’s his name?”

“Hrawlf.”

“That sounds like a dog’s bark. I think I’ll call him ‘Grumpy,’ instead.”

A large pot hung on a hook in the huge fireplace above glowing coals and embers. Lazy steam rose from its interior. Hildegard walked over to the pot and looked at the viscous dark brown liquid bubbling fitfully within.

“What do you call this?,” she asked.

“Stew.”

“That’s it? What about ‘beef stew’ or ‘vegetable stew’? What’s in it?”

“I don’t know.”

Hildegard began opening doors to pantries and cabinets. They were all empty. “Where’s the food?”

The barkeep motioned to the cheese and bread in the middle of the room. “Right thar on the table.”

“That’s it? Moldy cheese and mildewed bread? Where’s your veggies, where’s your spices, where’s your fruit, where do you keep your dairy products?”

“Dairy products? Fruit? Spices? Veggies? What’re you talking about, woman?”

Hildegard sighed. She did a lot of sighing around men. “Listen, I have a name. It’s Hildegard, although my friends call me ‘Hildy.’ I suggest you use it if we’re going to get along. Now, what’s your name?”

“Lrol’nash’wa.”

“Ugh. That’s too weird and unpronounceable. I’ll call you ‘Scrawny.’ So, Scrawny, have you ever had a steak? An omelette? A salad?”

“A steak? An omelette? A salad?”

“Maybe I should call you ‘Echo,’ instead of ‘Scrawny.’ It looks like you really need a woman’s touch around here.”

Then Hildy saw a room leading off the far side of the kitchen. It had no door, but there was a line of large asterisks painted across the floor leading into it. “What’s this?”

Scrawny blushed and looked at the floor. “Ah, that thar’s the room, ah, the room the barmaid used, when we had a barmaid. She left a long time ago.”

“What’d she use it for?”

“Well, uh, you know....”

Hildy smiled. “Yeah, I know. I told you I wasn’t a Virgin. Yell for Grumpy to get his runty butt in here, and then you come over here.”

Scrawny, still in the doorway, turned to the inn’s main room and yelled, “Grumpy! I mean, Hrawlf! Hildy says for you to get your runty butt in here!”

Then Scrawny walked slowly, cautiously, across the kitchen to where Hildy was standing before the door with the line of asterisks. Hildy picked him up in both arms and held him to her ample bosom. “Like I said, Scrawny, what you boys really need around here is a woman’s touch.”

Grumpy appeared in the kitchen’s other doorway just in time to see Hildy, with Scrawny in her arms, step across the line of asterisks into the barmaid’s room. “Don’t worry, Grumpy,” Hildy called to him. “You’re next.”

*

Utthar crawled out of the stable haystack where he’d spent the night after mucking out the cesspool. He fearfully approached the inn. Loud howls of laughter and mighty oaths had come from the inn all night. He quailed at the thought of what the Chain Gang might have been doing to Hildy, but he dared not intervene, lest both their lives be forfeit.

As he rounded the front corner of the inn, he saw one of the Chain Gang on a ladder, oiling the new sign which hung above the door. “The Dew Drop Inn - Bed & Breakfast,” it read in bright new lettering. “Thar,” the ruffian said, experimentally pushing the sign. “Now it doesn’t squeak!”

Puzzled, Utthar walked to the inn’s door. Above the door, in fresh new paint, the word “Welcome” arched over the doorway. He pushed open the door and stepped inside. He gaped at what he saw. The room had been swept clean of all debris, intact tables and chairs, showing signs of sturdy repair, dotted the room. Even more amazing were the Minions of the Dark Lord. Their beards were neatly trimmed and some were even clean-shaven. All had combed their hair and some had even cut their hair. They were busily sweeping, dusting, bustling hither and yon on various errands.

Behind the bar the barkeep was carefully drying glasses and stacking them in neat pyramids. He glanced over at Utthar still standing in the doorway. “Welcome, Mr. Utthar! I hope you had a pleasant night in the stable?”

“Uh, it was acceptable. Where’s Hildy?”

The barkeep waved toward the kitchen. “She’s overseeing breakfast. Would you like an omelette? Go right in!” He returned to his glass pyramids, whistling cheerfully as he daintily placed a last glass on the apex of one of them.

Utthar walked across the inn’s main room, carefully stepping around the Minions at their various tasks, until he stood at the kitchen doorway. The homey smell of bacon and eggs wafted around him. The kitchen was a clean and neatly organized space with more Minions bustling about. At the large roaring fireplace the Dwarf who’d threatened him at dagger point was dressed in a white apron. With a thickly padded mitt he held a skillet over the fire. Huge quantities of eggs were sunny-side up in the skillet’s sizzling bacon fat. The Dwarf looked over at him and smiled beatifically. “Good morning, Mr. Utthar, I hope you slept well. How would you like your eggs?”

“Only after he takes a bath,” Hildy interrupted. “He stinks like a cesspool.”

Utthar saw Hildy standing in the midst of the kitchen, crisply directing Minions in their myriad tasks.

“Hildy, what’s going on here?”

Hildy smiled at him. “It’s just as you said, husband of mine. The Lord works in mysterious ways, but the Lord does provide. I don’t know about you, but my pilgrimage is at an end. I’ve found the Promised Land!”

Standing in the doorway, stinking of the cesspool, Utthar gazed at all the Minions of the Dark Lord heeding Hildy’s beck and call with eager steps.

And he knew he should’ve turned right instead of left at that last crossroads.

Copyright © 2016 by Eric Leif Davin.

ONE SALE NOW

Nina Kiriki Hoffman is the author of more than two hundred stories, a Nebula winner (and multiple Nebula nominee), a Bram Stoker winner, and a Locus Award winner. This is her first appearance in Galaxy’s Edge.

MARROW WOOD

by

Hew Avery da Silva had had his ears docked and his eyebrows reshaped three planets and four lifetimes ago, when the last known member of his race killed herself. Better to blend with the larger mass of somewhat human population, he felt, not knowing that a fashion for pointed ears and winged eyebrows would sweep the cultureweb, and even youngsters on the backwater colony planet where he lived at the time would shift their looks toward his. How strange was that, his looking the way they were born to, and they looking like members of his race? But it was a passing fad, and just as well he’d revised his looks before it came and went.